What Do We Mean By Regional Democracy?

This essay is taken from our book What Kind of Region Do We Want To Live In?

Download a pdf copy of the book.

Regional democracy is a political theory and practice developed in West Yorkshire. It identifies three complimentary and interconnected fields: region building, radical subsidiarity and overcoming the London hegemony.

Building a region

The first field of regional democracy is cultural: the construction and maintenance of the idea of a region as a space for co-operation between people and places, and the opportunity of fair and equal participation in that co-operation by everyone who currently lives in the region, no matter where they or their relatives were born.

England, and the wider UK, has no meaningful history of federal regional governance so constructing regional democracy here begins with a process of 'conscientisation', which is “the process whereby people become aware of the political, socioeconomic and cultural contradictions that interact in a hegemonic way to diminish their lives” 5. This Paulo Freire idea also includes “taking action against the oppressive elements in one's life that are illuminated by... understanding” that hegemony 8.

Our first act of conscientisation in West Yorkshire was an Open Space event in Manningham, Bradford in 2015, which asked the question 'What Kind of Region Do We Want to Live In?'. From the beginning we have been open to working with people from all parties and none and we have actively tried to do something to engage a more diverse range of voices. This means being open to different ways of working including participatory art projects and events based on open models with no fixed agenda and no top table of speeches (such as from MPs or council leaders) so enabling all participants to suggest themes/discussions with equal value. It also means thinking about when, where and how events happen so that it is not just about women and men who already hold positions of power within the region. This includes offering childcare and helping with travel costs.

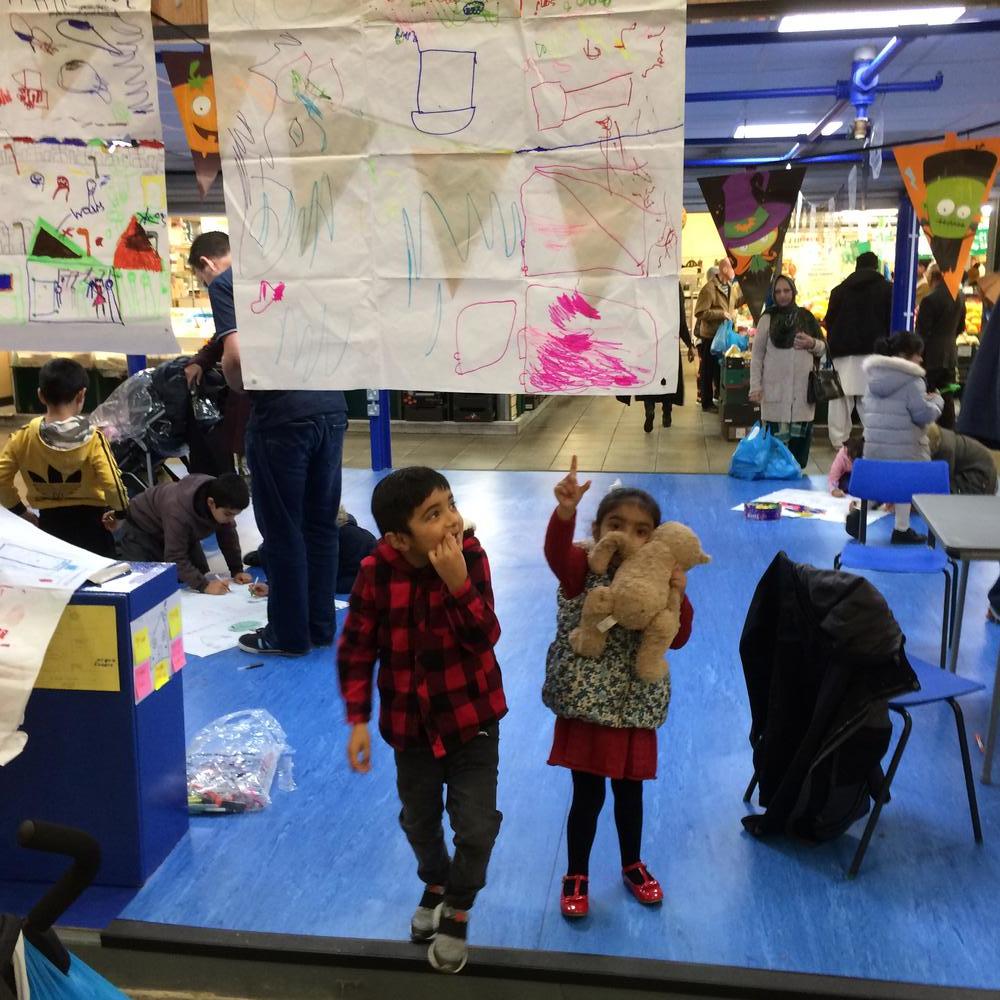

Following our first event, we began the 'We Share The Same Skies' collaborative blog of hopeful ideas and since then, we have developed and delivered more creative 'conscientisation' projects including a viral sticker campaign that invited people to think over provocative questions on the subject of regional democracy, most notably 'How come places in West Yorkshire are run by people in London?'. We've also undertaken a participatory art project in which we visited all the major markets of West Yorkshire, asking people shopping there to create maps of their communities, and talking about how they relate to their communities and region.

The aim of these activities is to engage people in region-building and not just resistance, cynicism or scepticism. We believe the bottom line is that a centralised UK has failed us and that the idea of regional democracy represents a positive opportunity. If we actively try to make it so. We are specifically committed to focusing our work around the 'margins', helping to generate a movement that not only critiques London as an inappropriate centre of power, but also takes the debate out of the established centres of subsidiary power in our region - the town halls, the voluntary sector, etc. We believe this is the next step in building a more positive politics for the region.

Radical Subsidiarity

The second field of regional democracy is the design and implementation of a governance architecture for where we live in which the regional scale sits between the local and the national. This regional scale has two roles, one inward facing, one outward. The inward facing role is to be the space for co-operation between people and places outlined above, and formally this covers things like transport, education and skills, healthcare, major cultural venues (including sport and parks), the environment, local taxation, planning laws, regional banking, making and managing relationships with other regions nationally, in Europe and worldwide, and so on. The outward facing role, crucially missing in the recent historical context of England and the UK, is to counterbalance London's hegemony.

In regional democracy all authority and responsibility for governance flows from the foundational scale upwards, and by only as much as is granted by one level to the level above. At the lowest level, we believe that the culture of regional democracy is a culture of governance participation at an interpersonal, face-to-face scale, embodied in the formal structures of local and regional government, and also, just as vitally, embodied in participatory and deliberative democracy at a neighbourhood level, in the economic democracy of cooperatively-run businesses, in clubs and societies, arts and sports organisations, governance and delivery of public services, the stewardship and enjoyment of the natural world, and not least local commercial businesses in their relationships with customers and each other. Governance of a regional democracy is the shared responsibility of each of us in our everyday conduct: to mindfully look for opportunities to work together to maximise the benefits of what we have in common, while respecting and valuing our differences.

Governance architectures based on similar principles are commonplace around the world. German federalism, for example, includes a Bundesrat, made up of representatives from the government in each Land (people sent to Berlin to stand up for their region) and the Bundestag, made up of directly elected representatives from across the republic (similar to our MPs). Representatives in the Bundestag reflect the fact that within each Land, and across the republic as a whole, there are a diversity of opinions. Within this well defined and transparent governance architecture, some decisions (default competencies) are made by the Land government autonomously and are implemented within its own space only. These are substantial powers, for example German regions can make their own choices about student tuition fees. The German system was created by British civil servants after the Second World War in order to prevent the concentration of power. The same civil service went on to write and impose dozens of constitutions on other countries as they gained national independence from the British Empire. In contrast, English exceptionalism meant the same principles were never applied here 3. The space governed as England has no transparent rule book to define the relationship between different parts of the country. Why not? And who benefits from that?

Actively Challenging London's hegemony

The third field of regional democracy is an analysis of who benefits from things as they are, and how we can overcome that. Anyone doing such an analysis will find themselves naming the negative impact of London's hegemony on the UK, especially the impact on people and places outside London and the Home Counties, and in particular the most vulnerable. Regional democracy seeks to actively challenge that hegemony in what Sharon White (second permanent secretary at the UK treasury) described as “the most centralised developed country in the world” 1.

In this specific context, hegemony means the dominance of a way of thinking, doing and being that is most closely associated with a specific region of the UK and which is exactly the same place where overwhelming political, economic, cultural and media power is concentrated – London and the Home Counties 7. This hegemony is derived from London's position as a colonial capital city and its history of financial capitalism. In “British Imperialism: 1688-2015” historians Peter Cain and Tony Hopkins 2 describe the co-evolution of the City, Whitehall, and Westminster into what they call "gentlemanly capitalism", focused on the generation of wealth through finance. This was separate from the financing of Britain's industry, which was done by regional banks, rather than the City of London. Instead the City focused on exporting finance to Britain’s colonies and extracting wealth from them. An ongoing legacy of this imperialism is the way the City, Whitehall, and Westminster treat the rest of the UK. Hemsworth MP and former Leeds City Council leader Jon Trickett described this as the UK government treating “us like the last colonial outpost of British Empire.” 10

Whether it is about spending money (such as prioritising and investing in London’s schools or infrastructure over other parts of the UK) or it is about creating a political and legal climate (such as one that benefits types of industries concentrated in London but not one that benefits types of industries concentrated elsewhere), London continues to be economically successful because UK government has decided actively to do something to make it so 6. Each time these decisions are successful, they strengthen London’s case for being prioritised in the future, based on a self serving return-on-investment metric 4.

It is important to say that this analysis is about structure and systems rather than a conspiracy of people in London setting out to be deliberately vindictive to people outside London and the Home Counties. It is the inevitable consequence of the Londoncentric UK structure that leads to concentrations of power amongst those who cannot help but share some key experiences and therefore perspectives. In fact, we respect the analysis of those Londoners who also wish to challenge the London hegemony and describe how it fails the vulnerable of London itself. Nevertheless we would continue to critique those London based organisations who claim to organise nationally or offer a national perspective or service but whose hub and franchise structures mean they retreat there when resources are stretched or who continually expect people to travel to meetings or events in London as easily as the many other people based in the Home Counties. Such approaches merely perpetuate the London hegemony.

John Tomaney, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning in the Bartlett School of Planning, called this “a (post)colonial cultural relationship” between London and other regions 9. Poltical parties, national charities, national arts organisations and museums, the health service, trade unions and business associations all have the same hub and franchise organisational model: good jobs and careers deciding policy in London, badly paid jobs and volunteers doing what they are told everywhere else. This applies just as much to the institutions of the Left as the Right. The English Labour Party is itself a product of the London hegemony, the victory of the statism of the Fabians, who were a small group of well connected London journalists, over the freewheeling, cooperatively-minded and regionally rooted Independant Labour Party 11.

Regional democracy challenges the London hegemony not just in order to overcome its negative impact but to give people across the country, rather than just those in London, the agency to campaign for, and make, positive changes where they live and work. Changing a national policy inevitably focuses on campaigners, politicians and civil servants based in London, if only because that is where the decision is made. Those conversations bypass people in other regions because it's more time consuming and expensive for us to be involved in them. A one hour meeting with a civil servant or to attend a protest is a day's commitment at least.

If we overcome the London hegemony, and root political authority where we live and work, it means that people in West Yorkshire (and in equivalent regions in other parts of the country) who have a vision for positive change can much more easily work together to influence decisions about their lives. Regional democracy releases new energy, generates new ideas and makes it easier for many voices to get heard.

Join us?

This is our theory, this is our practice. Will you join us to build regional democracy in West Yorkshire? Will you join with others to build regional democracy where you live?

-

Winnie Agbonlahor. 2015. UK ‘almost most centralised developed country’, says Treasury chief. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from https://www.globalgovernmentforum.com/uk-most-centralised-developed-country-says-treasury-chief/ ↩

-

Peter Cain and Tony Hopkins. 2014. British Imperialism: 1688-2000. Routledge, London. ↩

-

Linda Colley. 2014. Word Power: written constitutions and the definition of British borders since 1787. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from http://www.lse.ac.uk/lse-player?id=2343 ↩

-

Tom Forth. 2017. The fiscal balance of power. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from http://tomforth.co.uk/fiscalbalance/ ↩

-

Margaret Ledwith. 2005. Community Development: A Critical Approach. Policy Press, Bristol. ↩

-

Manchester Capitalism collective. 2012. If They're London's Revenues, They're London's Liabilities. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from http://manchestercapitalism.blogspot.com/2012/12/if-theyre-londons-revenues-theyre.html ↩

-

Philip McCann. 2016. The UK's Regional Problem. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from https://www.centreforcities.org/event/city-horizons-professor-philip-mccann/ ↩

-

Elena Mustakova-Possardt. 2003. Critical Consciousness: A Study of Morality in Global, Historical Context. Praeger, Westport, Connecticut / London ↩

-

John Tomaney. 2018. From the Lindisfarne Gospels to Stephenson’s Rocket: The case for a National Museum of Northumbria. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from https://www.citymetric.com/horizons/lindisfarne-gospels-stephenson-s-rocket-case-national-museum-northumbria-4094 ↩

-

Jon Trickett. 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2019 from https://twitter.com/jon_trickett/status/900110699799736326 ↩

-

Paul Salveson. 2012. Socialism with a Northern Accent: Radical Traditions for Modern Times. Lawrence & Wishart, London. ↩

Understanding The Challenges: South Asian Muslim Mental Health in West Yorkshire

The early teachings of Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him) highlight the basic equality of all human beings, laying the groundwork for an …

Sharing Umbrellas Part 2: An Interview with Landscape Architect Bridget E. Snaith

In the second part of Sharing Umbrellas, her report on our West Yorkshire Walks in Harehills, Leeds, in July 2023, Vivien De Brito interviews landscape …

Themes, Quotes and Links from the Decent Homes and Liveable Places #2 online event

This is a summary of the main points from our second "How do we create decent homes and liveable places for all in West Yorkshire …